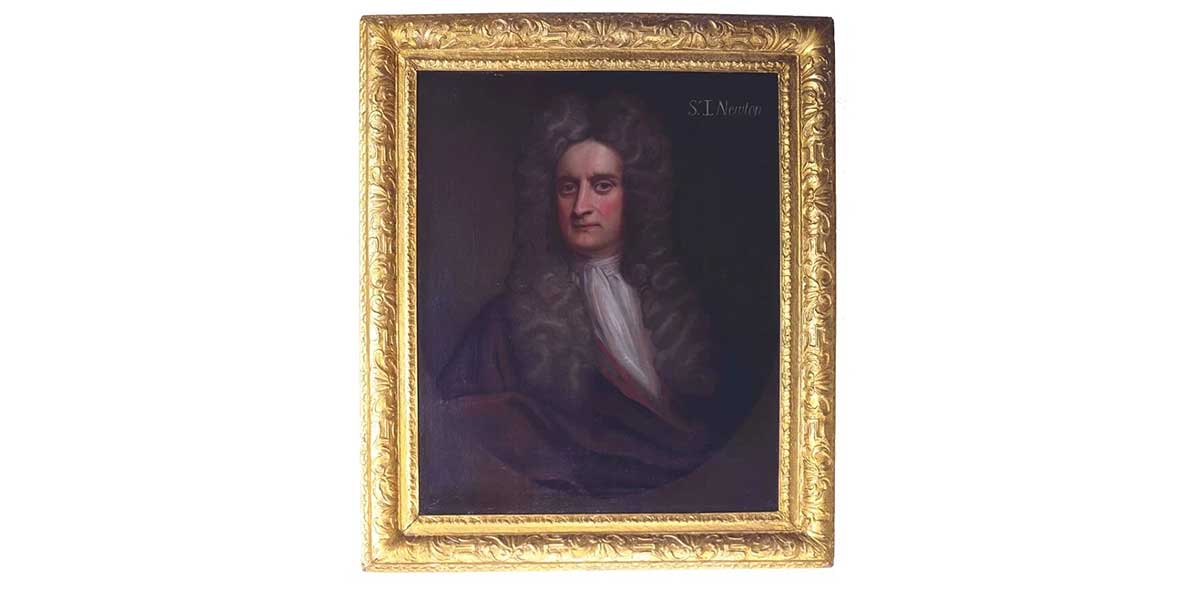

Sir Isaac Newton and The Royal Mint

Commemorative • The Great British Treasure Hunt

Isaac Newton was appointed Warden of The Royal Mint in the spring of 1696 on the recommendation of Charles Montague, Chancellor of the Exchequer. Public office was new to him, but nevertheless it was an opportunity which he had sought, and Montague’s letter of 19 March 1696 notifying him of the king’s promise of the vacant post of Warden would not have been unwelcome.

The Royal Mint was then in the Tower of London and it was according to the Tower that Newton came in April 1696 to take up his new duties. It was a time of great activity, for The Royal Mint was grappling with the recoinage of old silver coins dating back to the reign of Elizabeth I and beyond. Auxiliary mints were being set up in various parts of the country, and Newton was quickly caught up in the pressure of the moment. The enormous operation was completed within three years, leaving Newton more time to devote to his main duty of investigating and bringing to justice those who clipped and counterfeited the coin of the realm.

Appointment as Master

In 1699 the post of Master of The Royal Mint fell vacant by the death of Thomas Neale. Though technically less senior than that of Warden, it was a more lucrative post because the Master acted as a contractor to the Crown and profited from the rates at which he put the work out to sub-contractors. The Mastership was offered to Newton and he took up its duties with effect from Christmas Day 1699. Surviving the political upheavals of those troubled times, he remained as Master until his death in March 1727.

Active Involvement

It was plainly a time when, if Newton chose, there were important questions requiring his supervision and judgement, practical control and administrative skill. And from the start there is no doubt of an active involvement in the affairs of The Royal Mint.

- He is known to have himself conducted interviews with criminals and informers

- He was present when treasure captured from the French and Spanish fleet at Vigo Bay was brought into The Royal Mint

- The Scottish Mint in Edinburgh acknowledged with gratitude the friendly assistance they received from him after the Union in 1707

- His famous report of 21 September 1717 paved the way for a reduction in the value of the guinea to the familiar 21 shillings

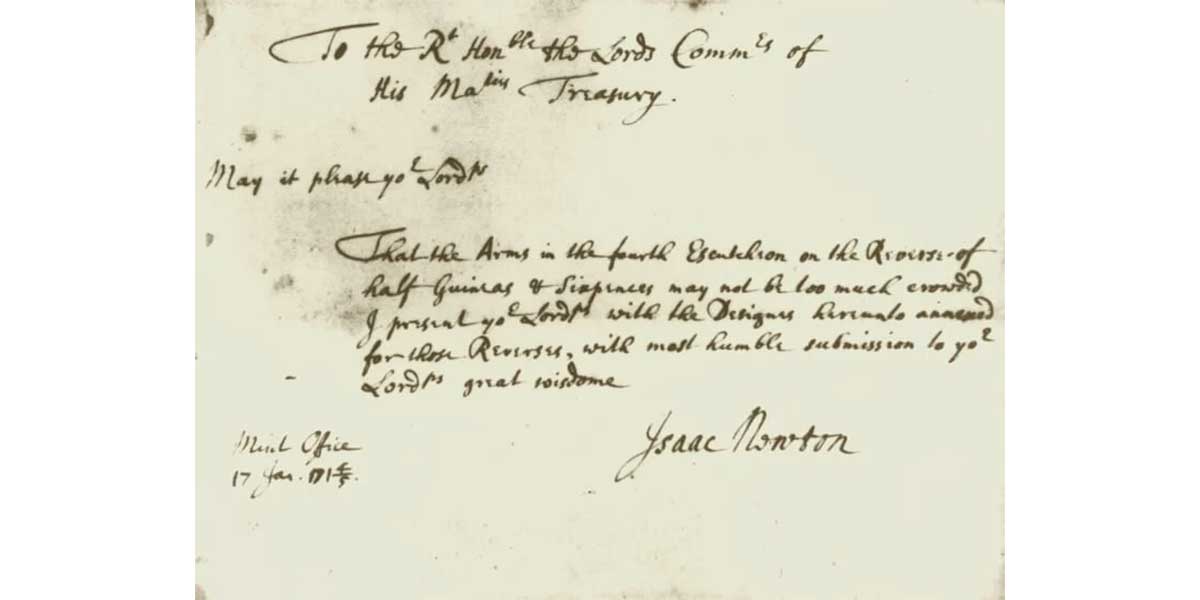

- He supervised experiments on the purity of copper, and some believe that he may even have carried out his own assays of gold and silver · Above all, the evidence of his activity is there to see in the hundreds of surviving draft reports and letters, written in his own hand and often many times over

Administrative Skill

Newton’s long-term contribution to The Royal Mint nevertheless seems in retrospect to be small for the greatest mind of the age. Such a view does not conflict with Montague’s assertion that the success of the Great Recoinage was due in great measure to Newton’s able administration, but it runs counter to the claim of the historian Macaulay that Newton speedily produced a complete revolution within The Royal Mint. On the contrary, he left The Royal Mint in 1727 very much as he found it 30 years before. Good administrator as he may have been, he was not an innovator and in his own words was far more comfortable in the search for precedent than in ‘embarrassing initiative’. The medieval organisation of The Royal Mint was therefore left intact.

Concern for Accuracy

Yet if there is no major reform of The Royal Mint with which his name can be associated, there was nevertheless a real and positive contribution. It is a contribution which shows itself especially in a concern for accuracy, for Newton wanted coins to be made of the correct weight and fineness, varying as little as possible one from another. Such accuracy was unprecedented and, with justice, Newton claimed that he had brought the coinage to a ‘much greater degree of exactness than ever was known before’. In these circumstances it is no wonder that he reacted angrily in 1710 to the mistaken judgement of the jury at the Trial of the Pyx that his gold coins were below standard.

Industry and Integrity

A second aspect of his contribution was his undoubted industry. Although he had able deputies, he chose not to delegate everything, providing a welcome change from his predecessors. And finally, and more important still, there is his integrity. He was an honest and respected man who cared for his reputation and who, as in his scientific disputes with Flamsteed and Leibniz, passionately resented reflections on his moral integrity. He is said to have refused a bribe of over £6000 in connection with contracts for the coinage of copper, and there can be no doubt that he set a high standard at a time when corruption was rife.

With thanks to The Royal Mint Museum

Isaac Newton and the 1710 Trial of the Pyx

As one of the most renowned scientific minds in history, Sir Isaac Newton’s influence extended far beyond the realms of mathematics and physics. When he assumed the role of Master of the Mint in 1699, Newton brought his legendary precision and intellectual rigour to the nation’s coinage, transforming a post-restoration mint into a model of integrity and innovation.

Although the office of Master of the Mint had traditionally been symbolic, Newton approached his responsibilities with a reformer’s zeal. He encouraged engravers to refine their artistry by undertaking private commissions, raising both the standard and aesthetic of British coinage. At the same time, he pursued counterfeiters with forensic diligence, personally overseeing prosecutions to ensure the security and trustworthiness of the nation’s currency.

It was therefore all the more remarkable when his coins were called into question during the 1710 Trial of the Pyx, the formal ceremony in which newly issued coins were tested for weight and fineness. The results appeared to suggest that Newton’s gold coins fell short of the prescribed standard. Unwilling to accept such a claim at face value, Newton investigated the process himself and discovered that the fault lay not in the coinage but in the new Trial Plate introduced in 1707. The plate, against which the coins were measured, contained more gold than required, leading to the erroneous conclusion of deficiency.

Following Newton’s findings, the older 1688 Trial Plate was reinstated, restoring confidence in both the coinage and the exacting processes of The Royal Mint. The episode stands as a testament to Newton’s unwavering commitment to precision and fairness, principles that continue to define The Royal Mint today.