The development of the Waterloo Medal has been well documented, both through The Royal Mint’s archives and external sources. A design imbued with intricacy and ornate detail, it is understandable how it could take an artist three decades to perfect, especially one so committed to originality as Benedetto Pistrucci.

However, there were external factors which influenced the painstakingly slow progress of the highly anticipated medallion. Despite assuming the responsibilities of Chief Engraver and carrying out many of the duties associated with the role, Pistrucci could never fulfil the role in an official capacity due to a law decreed by William III, which debarred a foreigner from assuming the position. His frustration was even more exacerbated when William Wyon RA, who once served as Pistrucci’s junior, assumed the role of Chief Engraver, with the Italian given the position of Chief Medallist. Embittered at what had occurred, Pistrucci played an active role in slowing the work on the medal to ensure his financial security, despite insisting to William Gladstone, then Master of the Mint, ‘it is impossible there can be in this world any one individual more anxious than myself, to see the Waterloo Medal finished.’

Thirty Years in the Making

Following a suggestion from his younger brother, the Duke of Wellington, William Wellesley Pole approached Pistrucci to create designs for a medal commemorating the Battle of Waterloo. The work began in 1819 but it wasn’t until 1849 that the dies were delivered to The Royal Mint. They were so large they couldn’t be hardened, so the medal was never physically struck, and the electrotypes were the only fruit of Pistrucci’s 30-year labour.

Nevertheless, these electrotypes bore the medal’s design, which is one of inimitable intricacy and consummate detail. Layered with allegorical meaning, the artist has interpreted the Battle of Waterloo through a classical lens, as the design entwines gods and figures from Greek mythology with the events of the battle itself.

The Obverse

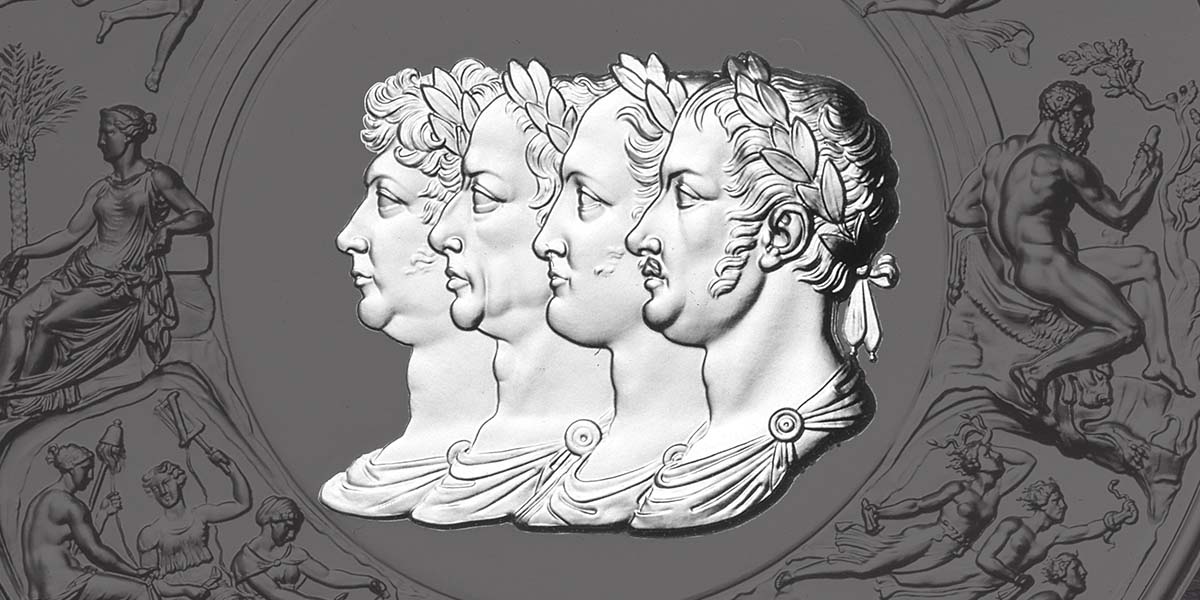

The general design of the medal is treated allegorically, except the central part of the obverse, which represents the busts of the four allied monarchs, seen grouped in profile to the left: George, Prince Regent; Francis II (Emperor of Austria); Alexander I (Emperor of Russia); and Frederick William III (King of Prussia). An array of figures feature in the border framing these portraits, in a thoughtfully constructed tapestry which constitutes an allegorical and mythological allusion to the Treaty of Peace which resulted from the great triumph in the field of battle.

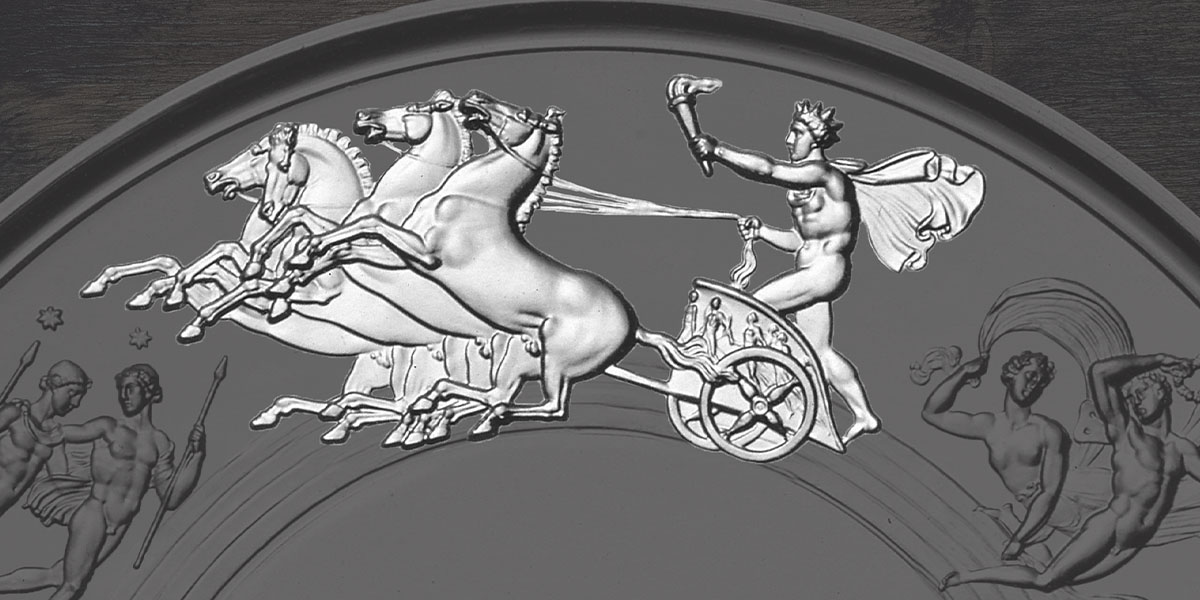

Apollo is presented at the top of the obverse in his quadriga restoring the day.

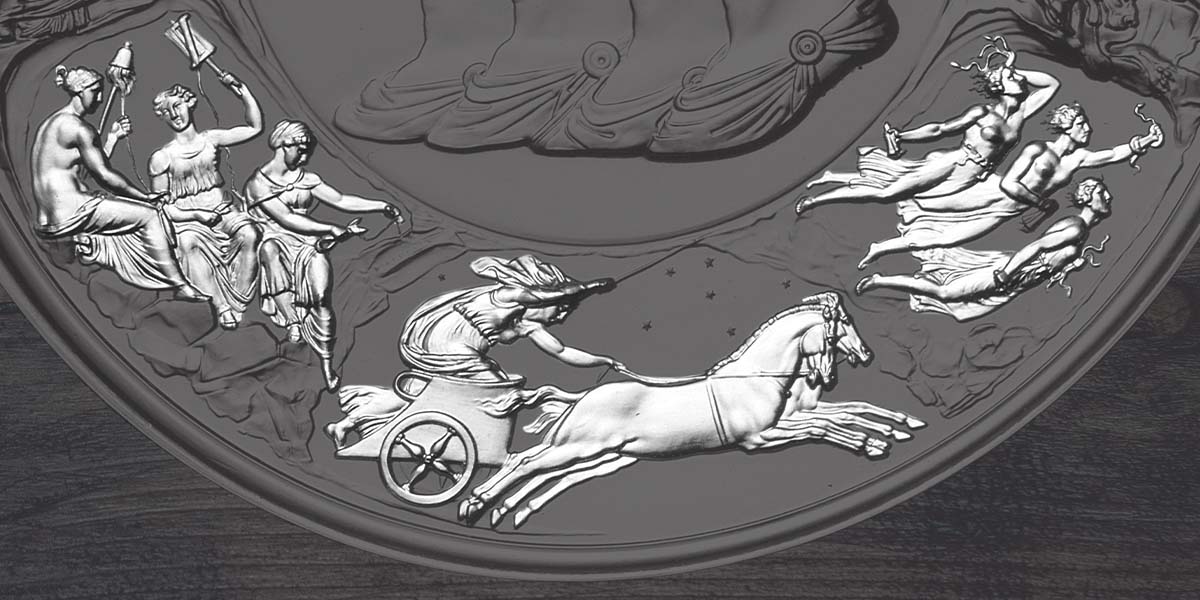

The rainbow Zephyr and Iris follow the chariot of the sun in succession, but the Zephyr is tending towards the earth and scattering flowers as a symbol of peace and tranquility.

The chariot hurtles towards the constellation Gemini and therefore symbolises the month in which the great contest took place. Castor and Pollux, with spears, represent the apotheosis of Wellington and Blücher; Themis, the goddess of Justice, appears on earth, as in the golden age.

This figure is placed in front of the profile busts of the sovereigns, to show that justice is a greater security to the government than power. The goddess is seated upon a rock, with a palm tree waving overhead; she is prepared to reward virtue with its branches in one hand, and in the other she holds a sword for the ready punishment of crime.

A robust man of mature age, bearded, and armed with a club, personifies Herculean power. He is seated under an oak tree and forms the corresponding figure at the back of the group of busts of the allied sovereigns.

SHOP ALLIED LEADERS

Own an Exquisite Work of Numismatic ArtSHOP ALLIED LEADERS