The Pleistocene Epoch, also referred to as the Ice Age, began around 2.6 million years ago, although the Earth had been cooling for much longer than this. This period saw vast glaciers, known as ice sheets, expand across the Earth’s surface and take up large swathes of land. The ice sheets extended beyond the North and South Poles, where they still exist today, and reached as far as the Midlands in England and across what is now Canada and the northern United States of America.

These ice sheets could be up to 3km thick and nearly all animal and plant life were excluded from the areas they covered. Contrary to popular opinion, the large mammals known as megafauna that lived during the Pleistocene Epoch did not live on these glaciers but rather in the southerly areas next to them, where plant life thrived and supported an abundance of life.

With a vast quantity of the world’s water frozen in these ice sheets, sea levels fell that resulted in animals roaming between different areas of land and species spreading to new habitats that had previously been separated by water.

The Steppe Mammoth

The elephant family – known as Proboscidea – dates to 60 million years ago and comprises three branches: Loxodonta, Elephas and Mammuthus. Today, relatives of Loxodonta can be found in the African elephant and the African forest elephant, whilst relatives of Elephas can be found in Asian elephants. The third branch – Mammuthus – includes several species of mammoth.

Mammoth fossils have been discovered across the world and it is through these remains that we can see an evolution in response to changing environments. This evolutionary change can be explored through the changes to molar teeth, skulls, jaws and other parts of the skeleton, with one of the most convincing examples of evolutionary change being the evolution of the steppe mammoth to the woolly mammoth of the Ice Age.

One of the largest megafaunas to roam during the Pleistocene Epoch, the steppe mammoth, or Mammuthus trogontherii, had an average shoulder height of 4 metres and weighed around 10 tonnes. This species of mammoth appeared in China around 2 million years ago, with an increase of ridges in its back molars to give greater resistance to abrasive foods. These molars were also increased in height so that they would last for the lifespan of the mammal. Jaw bones were deepened to accommodate these larger teeth and the steppe mammoth also had a taller head than its predecessor Mammuthus meridionalis.

The steppe mammoth spread across Eurasia as climates cooled and habitats opened. The first mammoth species to spread beyond the Arctic circle, numerous steppe mammoth remains have been discovered across the far north-east of Siberia and through these we can see how the final stages of evolution to the woolly mammoth took place.

Some of the earliest woolly mammoth remains date between 800,000 and 600,000 years old and display higher-crowned molar teeth with further increases to their number of enamel ridges. Although there are a limited number of soft tissue samples to examine, it is reasonable to assume that as the steppe mammoth moved to colder climates it developed the longer and thicker fur of the mammoth species that we see within popular culture.

One of the most significant discoveries of a steppe mammoth skeleton in the United Kingdom is the West Runton mammoth. In 1990, a couple walking on West Runton beach in the county of Norfolk in England spotted a large bone sticking out of the cliff face. This was later revealed to be the pelvic bone of a steppe mammoth, whilst further excavations unearthed 85% of a steppe mammoth skeleton. This was the most complete skeleton to be discovered in the United Kingdom and was also a very well-preserved example. It is estimated that this 700,000-year-old skeleton is a 41-year-old male with a body mass of around 9 tonnes and a shoulder height of approximately 4 metres.

In 1864, naturalist Antonio Brady discovered a complete steppe mammoth skull in Ilford, London. The most complete mammoth skull to be found in Britain, it featured tusks that were 3 metres in length.

The Woolly Rhinoceros

One of the largest mammals to exist alongside mammoths was the woolly rhinoceros, or Coelodonta antiquitatis. This giant herbivore was similar in size to a white African rhinoceros and weighed around 2 tonnes.

Unlike its modern relatives, the woolly rhinoceros had a thick coat to keep it warm in the cold, grassy plains where it would have lived. Its wool coat was made up of a double layer – the long hairs on top formed a protective layer, whilst the shorter hairs underneath formed a thermal layer. Whilst it is not known what colour this fur would have been, we know from preserved carcasses that it would have had a thick mane.

We can tell that the woolly rhinoceros was adapted to survive in the colder temperatures of the Ice Age, living in temperatures as low as -60°C. Its body was stocky and its short legs, short ears and tail helped prevent unnecessary heat loss.

The woolly rhinoceros had two horns that were made from compressed hair. The front horn could reach up to 1.2 metres in length and became flattened from side to side to form a ‘V’ shape, which is thought to be from clearing snow in search of food. To fuel its large body, the woolly rhinoceros would have spent a large portion of its time eating. Preserved carcasses have shown that the woolly rhinoceros would have had wide, flat lips that allowed it to graze on a variety of low vegetation.

Although the woolly rhinoceros would have lived alongside the woolly mammoth at points, the population wasn’t as widespread as that of the larger mammal and it did not live in the northernmost parts of Siberia. An almost complete carcass of a woolly rhinoceros was discovered in a mine in Serbia, which had been well-preserved because of a -40°C climate.

In 2002, a rare partial skeleton was discovered in the valley of the River Tame at Whitemoor Haye in Staffordshire, England. This carcass was exceptionally well preserved and the bones were in excellent condition, making this one of the best examples of a woolly rhinoceros to be discovered in the UK in the twenty-first century. Thirty-three individual elements were identified from this partial skeleton, including a complete skull, vertebrae and ribs, and it is from examples such as these that we have been able to learn more about the woolly rhinoceros and the time in which it lived.

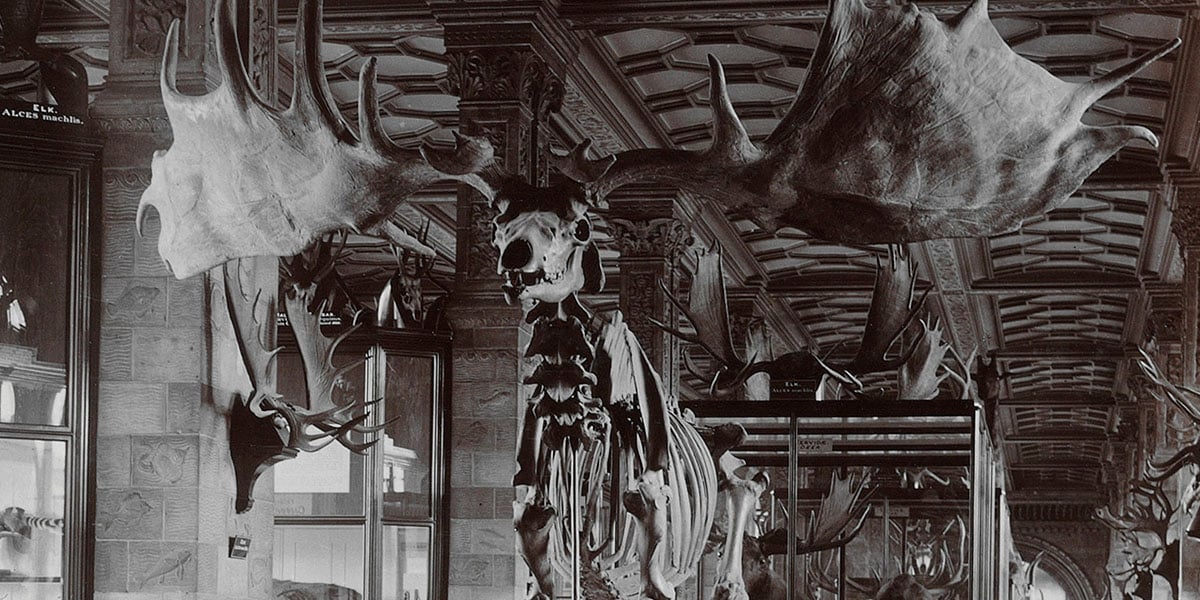

The Giant Deer

One of the last megafaunas to have lived during the Ice Age was the giant deer, or Megaloceros giganteus. Although the giant deer coexisted with the woolly mammoth, this species also lived in more southerly areas during periods when the woolly mammoth and woolly rhinoceros would have been absent until climate change affected the giant deer’s ability to survive.

The giant deer had an impressive standing shoulder height of just under 2 metres, the height of the average doorframe, and weighed around 500 kilogrammes. Its most impressive feature was the massive antlers that were grown exclusively by the males. These could range from 3.5 to 2.5 metres depending on the age of the animal, growing in size and complexity as the males aged.

Antlers were made from solid bone and examinations of antler bones show significant strengthening along the front edge, which suggests they were used for fighting rather than display as was first thought. They were shed in the spring and then regrown throughout the summer months ready to be used for fighting in the autumn and winter. Females would gather to watch males compete by roaring and it is thought females found larger antlers more desirable, leading to larger antlers through sexual selection.

These vast antlers made it difficult for them to move through dense woodland so instead they preferred flat plains, lightly wooded areas and grassland. Giant deer would have grazed on rich vegetation such as grass and soft leaves and this environment would have encouraged the growth of their large antlers.

Some cave paintings depict the giant deer with a ring around its neck, diagonal lines down its body and a strong back hump over its shoulder that would have been dark in colour compared to the rest of its coat. The fossils of giant deer show an extra thickness along the top of the skull as well as very sturdy neck vertebrae that along with the hump on their back would have helped to support the weight of their impressive antlers.

The first wave of extinction for the giant deer from Ireland, Britain and most of Europe happened around 12,000 years ago. The climate had become very cold and the scarcity of food would have made it difficult for the giant deer to adapt. However, remains have been found in Russia that date back to around 8,000 years ago, which is much later than the giant deer was thought to have become extinct.

In contradiction to the first extinction, it is thought that opposite climate conditions are to blame for this second wave of extinction for the giant deer. As climates began to warm, forests began to spread, which left less grassland for the giant deer to roam. It is thought that growing human populations could have also been a factor as expanding settlements would have taken over large areas of natural vegetation, as well as hunting by these Neolithic people.

Towards the end of the Ice Age, conditions in Ireland became perfect for the preservation of carcasses and fossils. Melting glaciers formed lakes, with the carcasses of giant deer sinking to the bottom and becoming covered in sediment. Further accumulations of peat meant that these carcasses were preserved over time until they were unearthed many years later. Because of various discoveries of giant deer in Ireland, it has often been called Irish elk, although it isn’t closely related to elk and remains have also been found across Europe and central Asia.

The Natural History Museum houses a partial skeleton of a giant deer that carbon dates to around 8,000 years ago. Discovered in the Oryol region of Eastern Russia, it is thought to be one of the last surviving giant deer and its remains include a right lower jaw, vertebrae and ribs amongst other elements.

Ice Age Giants

Examples of each of these impressive Ice Age giants can be found in the Natural History Museum collection. From the work of scientists such as palaeobiologist Professor Adrian Lister at the Natural History Museum, we have been able to learn so much about extinct species like the woolly mammoth. Through examination of the changes in molar teeth across various mammoth species, as well as the preservation of teeth and bones, we have been able to learn more about how these species adapted to survive in various conditions.

There are numerous theories as to what could have led to the extinction of megafauna such as the woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros and giant deer. For centuries, native peoples of the Arctic have been discovering preserved carcasses such as the woolly mammoth for centuries. It is thought that these large creatures lived underground and died on exposure to light, which would explain why none had ever been seen alive.

It is thought that climate change and hunting by Neolithic people would have also contributed towards the extinction of megafauna. Whilst hunting alone wouldn’t have been the sole factor, these larger beasts were slow to breed and had long gestation periods, so would have been affected by hunting over a longer period of time. A combination of hunting and changes to both habitats and climates had an impact on the population of these mighty herbivores. Whilst these mass extinctions happened a long time ago, we can learn something from them to help us conserve species today.

![]()